- Blog

- Programm

- Konkrete und Generative Fotografie

- Positionen aus Deutschland

- Zeitgenössisch International

- Czech Fundamental

- Shop Czech Fundamental

- Shop Czech Portfolios

- Ausstellung Czech Fundamental

- Eliska BARTEK

- Alfonse Mucha

- Jan Lauschmann

- Joseph Hnik

- Miroslav Tichy

- Ladislav Postupa

- Milos Korecek

- Petr Helbich

- Portfolio Jaromir Funke

- Frantisek Drtikol

- Vintages Frantisek Drtikol

- Portfolio Frantisek Drtikol

- Jaroslav Rossler

- Portfolio Jaroslav Rossler

- Editionen Jaroslav Rossler

- Jiri Sigut

- Nadia Rovderova

- Ales Kunes

- Suzanne Pastor

- Jan Saudek

- Villem Reichmann

- Josef Sudek

- Jan Svoboda

- Ladislav Emil Berka

- China

- Iberoamerikanische Fotografie

- EMOP 2025 Landingpage

- EMOP 2025 SHOP

- Artists

- Über uns

- AI-Edition

- Editionen

- Shop

CHEMA MADOZ

José María Rodriguez Madoz besser bekannt als Chema Madoz ist 1958 in Madrid geboren, wo er auch lebt und arbeitet. Er studierte Kunstgeschichte an der Complutense Universität von Madrid. Seine erste Einzelausstellung war 1983 bei der Royal Photographic Society of Madrid. Seit 1990 entwickelt er das Konzept der Objekte, ein Thema, das in seiner Fotografie bis heute immer wieder auftaucht. Die Fotografien zeigen auf subtile und ironische Weise paradoxe Welten von alltäglichen Gegenständen. Vertraute Objekte werden in einen neuen Kontext gestellt, jenseits einer Funktion – und erlangen durch das spielerische Zusammenspiel mit anderen Objekten eine neue Deutung. Diese assemblierten Konstruktionen spielen mit der Wirklichkeit, unserer Wahrnehmung und überhöhen sie - und setzen sie auf poetische Weise wieder frei.

Ende 1999 widmet ihm das Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía eine Einzelausstellung "Objetos 1990 - 1999", die erste Retrospektive dieses Museums für einen lebenden spanischen Fotografen. Chema Madoz hat eine Reihe von wichtigen Auszeichnungen und Ehrungen erhalten, wie z. B.: Kodak Spain Prize (1991), National Photography Award, Spanien (2000), Higasikawa Overseas Photographer Prize vom Higasikawa PhotoFestival, Japan (2000), PhotoEspaña Award (2000).

Seine Werke sind in vielen privaten und öffentlichen Sammlungen vertreten, darunter das Museo de Arte Reina Reina Sofía, Madrid; Colección Fundación Telefónica, Madrid; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Fonds National d`art Contemporain. París; DZ Bank Kunstsammlung u. a.

José María Rodriguez Madoz better known as Chema Madoz born in 1958 in Madrid, where he lives and works. He studied History of Art at the Complutense University of Madrid. His first individual exhibition was in Madrid in 1983, at the Royal Photographic Society of Madrid. Since 1990 he has been developing the concept of objects, a subject which would appear constantly in his photography until the present. The photographs show in a subtle and ironic way paradoxical worlds of everyday objects. Familiar objects are placed in a new context, beyond a function - and achieve a new meaning through the playful interaction with other objects. These assembled constructions play with reality, our perception and exaggerate it - and release it in a poetic way.

At the end of 1999 the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía dedicates him an individual show “Objetos 1990 – 1999″, which was the first retrospective show of this museum for a living spanish photographer. Chema Madoz has received a number of important awards and honors such as: Kodak Spain Prize (1991), National Photography Award, Spain (2000), Higasikawa Overseas Photographer Prize from the Higasikawa PhotoFestival (Japan) (2000), PhotoEspaña Award (2000).

His work is represented in many private and public collections, including Museo de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; Colección Fundación Telefónica, Madrid; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Fonds National d`art Contemporain. París; DZ Bank Kunstsammlung among others.

Visuelle Poesie

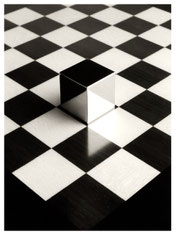

Der spanische Fotograf Chema Madoz fotografiert seit mehr als 20 Jahren gewöhnliche Objekte. Seine raffinierten Schwarz-Weiß-Fotografien zeigen gewöhnliche Objekte, die von Madoz selbst gewitzt manipuliert, aus dem ursprünglichen Kontext gerückt und zu einer neuen Realität zusammengefügt wurden, bevor sie fotografiert wurden. Das ist visuelle Poesie.

Die Welt der visuellen Paradoxien ist in der Tat ein Fest der Fotografie. Madoz kreiert seine eigentümlichen Objekte nur zum Fotografieren; er stellt sie nicht aus, sondern sie sind ausschließlich für die Kamera bestimmt. Diese (re)kontextualisierten Objekte laden Madoz' Fotografien mit Symbolen, Metaphern und doppelten Bedeutungen auf. Madoz konstruiert aus diesen Objekten eine neue fiktionalisierte Realität und dokumentiert ihre ephemere Existenz.

Madoz fotografiert ein Genre, das so alt ist wie die Kunst selbst. Stillleben steht seit der Höhlenmalerei im Fokus der Künstler und ist auch wiederkehrendes Thema in der Fotografie: William Henry Fox Talbot, Emmanuel Sougez, Joel-Peter Witkin, Wolfgang Tillmans oder Jeff Wall haben unter anderem Stillleben fotografiert. Aber Madoz' Fotografien (re)präsentieren das Genre mit einer ausgeprägten Rhetorik. Cristian Caujolle betont: Madoz' Werk artikuliert sich durch chimärische Objekte, die hinter ihrer regulären Erscheinung eine Fremdheit verbergen, die ihnen eine neue Wertigkeit verschafft, so Caujolle, dass Madozs Fotografien davon abhält, traditionelle Stillleben zu sein.

Tatsächlich ist das, was in Madoz' Arbeit wichtig ist, nicht das, was wir sehen, sondern das, was wir nicht sehen. Nicht das, was gezeigt wird, sondern die Art und Weise, wie Madoz' Fotografien verschiedene Elemente einführen und nutzen. Madoz' Fotografien brauchen unsere Teilnahme, um vollständig zu sein. Sie zwingen uns, zweimal darüber nachzudenken, was wir sehen, und dort, in unserem Intellekt, sind sie endlich vollendet und erfüllt. Diese Forderung nach unserer Mitwirkung, so könnte man sagen, behindert sie, dass sie still stehen bleiben. Anstatt Stillleben abzubilden, produziert Madoz "stille" Bilder.

Das Erste, was wir tun, wenn wir ein Foto sehen, ist die Erzählung, die Geschichte und das Argument suchen. Paradoxerweise ist das, was das eigentliche Wesen eines jeden Fotos ausmacht, das Verborgene oder nicht Gezeigte, das für unsere Interpretation und Vorstellungskraft Verbleibende. Wir schauen uns Madoz' Fotografien an, aber plötzlich stellen wir fest, dass sie etwas seltsam sind, und wir betrachten sie noch einmal nachdenklicher. Wenn wir Madoz' Fotografien erst einmal betrachtet haben, müssen wir sie nicht mehr anschauen, sondern nur noch an sie denken; sie sind installiert und verankert in unserem Kopf mit ihrer komplexen Einfachheit. Die Fotografien von Madoz sind nicht nur dazu da, um gesehen zu werden, sondern auch, um nachgedacht zu werden, um über sie zu meditieren und somit in allen Sinnen betrachtet zu werden. Und genau deshalb sind Madoz' Bilder so außergewöhnlich; seine bildlichen Paradoxien bedürfen unseres Verstands, unserer Meditation; sie sind geschaffen, um in unserem Geist vollzogen und vollendet zu werden.

Und hier arbeiten Madoz' Fotografien in Wahrheit, nicht auf dem Papier, sondern in unserem intellektuellen Engagement. Sie sind Instrumente des Denkens und Nachdenkens. Die Spannung zwischen dem, was das Auge sieht und was das Gehirn liest, macht uns als Betrachter zu einem wesentlichen Element von Madoz' Arbeit.

Als Betrachter sehen wir in Madoz' Fotografien Ähnlichkeit, wir sehen, was da ist und wie es ist, aber wir kontrastieren es auch mit dem, was wir wissen. Wenn Madoz' Fotografien als Täuschung wirken, dann nicht, weil sie uns täuschen, sondern weil wir uns hineinziehen lassen. Und wir tun das, weil wir sie auf den ersten Blick falsch verstanden haben; aber bald haben wir es erkannt und hören auf, sie falsch zu lesen, um genauer zu lesen, was wirklich da ist, ist das Foto, wie es ist, und nicht wie wir denken, wie es sein sollte oder wie wir dachten, dass es war. Tatsächlich sind Madoz' Fotografien atemberaubend, weil diese erste Fehlinterpretation, Ablenkung und Verwirrung, die durch Madoz' Geschicklichkeit hervorgerufen wird, ihre eigentliche Essenz ausmacht.

Pedro J Vicent Mullor

Eyemazing Magazin 02-2007

Visual poetry

Spanish photographer Chema Madoz has been photographing ordinary objects for more than 20 years. His refined black and white photographs show common objects that have been craftily manipulated by Madoz himself, placed out of their original context and joined together to create a new reality before photographing them. It’s visual poetry.

The world of visual paradoxes is, indeed, a celebration of photography. Madoz creates his peculiar objects only to photograph them; he doesn’t exhibit of use them afterwards, they exist exclusively for the camera. These (re)contextualised objects charge Madoz’s photographs with symbols, metaphors and double meanings. Madoz constructs from these objects a new fictionalised reality and documents its ephemeral existence.

Madoz photographs a genre that is as ancient as art itself. Still-life has been a focus for artists since cave paintings and has also been a recurrent theme in photography: William Henry Fox Talbot, Emmanuel Sougez, Joel-Peter Witkin, Wolfgang Tillmans or Jeff Wall, among an endless list, have photographed still-life. But Madoz’s photographs (re)present the genre with a distinctive rhetoric. As Cristian Caujolle points out: “Madoz’s work is articulated by deceptive objects which, behind their regular appearance, hide a strangeness which creates a new appreciation of them.” According to Caujolle, that new appreciation is what stops Madoz’s photographs from being traditional still-life.

In fact, what is important in Madoz’s work is not we see but what we don’t see. Not what is shown but the way in which Madoz’s photographs introduce and use different elements. Madoz’s photograps need our participation to be complete. They force us to think twice about what we see, and there, in our intellect, they are finally finished and fulfilled. That demand for our participation, it could be said, impedes them for being still. Rather than depict still-life, Madoz produces “still-alives” images.

The very first thing we do when we see a photograph is to look for the narrative, the story, and the argument. Paradoxically, what constitutes the true essence of any photograph is what is hidden or is not shown, what is left for our interpretation and imagination. We look through Madoz’s photographs but suddenly, we realise some oddity within them, and we look at them again more thoughtfully. Once we have examined Madoz’s photographs we don’t have to look at them again, we just have to think of them; they are installed and anchored in our minds with their complex simplicity. Madoz’s photographs are not made only to be seen; they are also made to be thought about, meditated on, and therefore to be, in all senses, contemplated. And that is precisely why Madoz’s images are so extraordinary; his visual paradoxes need our deduction, our meditation; they are created to be performed and concluded in our minds.

And this is where Madoz’s photographs in truth work, not on the paper, but within our intellectual engagement. They are instruments for thinking and reflecting. The tension between what the eye sees and what the brain reads makes us, as viewers, an essential element of Madoz’s work.

As viewers, we look resemblance in Madoz’s photographs, we see what is there, and how it is, but we also contrast it with what we know. If Madoz’s photographs work as a deception is not because they cheat on us, but because we let ourselves be taken in . And we do that because we misread them at first glance; but soon realised it and stop misreading them, to read more carefully what is really there is the photograph, as it is, and not how we think it should be or how we thought it was. Indeed, Madoz’s photographs are stunning because that first misreading, distraction and confusion, provokes by Madoz’s dexterity, constitutes their very essence.

Madoz’s photographs are titled “Untitled”, which is itself a paradox. In fact, by titling his photographs “Untitled”, what Madoz does is to paradoxically, (un)title his photographs. Madoz plays with the (visual) poetry of language and the complex simplicity of his (re) contextualised (re) presentations which, via resemblance and distraction, are performed in our intellect, leading us into a state of not only dual contemplation but of interaction; giving us, in any case, something we did not have before.

Pedro J Vicent Mullor

Eyemazing issue 02-2007