- Blog

- Programm

- Konkrete und Generative Fotografie

- Positionen aus Deutschland

- Zeitgenössisch International

- Czech Fundamental

- Shop Czech Fundamental

- Shop Czech Portfolios

- Ausstellung Czech Fundamental

- Eliska BARTEK

- Alfonse Mucha

- Jan Lauschmann

- Joseph Hnik

- Miroslav Tichy

- Ladislav Postupa

- Milos Korecek

- Petr Helbich

- Portfolio Jaromir Funke

- Frantisek Drtikol

- Vintages Frantisek Drtikol

- Portfolio Frantisek Drtikol

- Jaroslav Rossler

- Portfolio Jaroslav Rossler

- Editionen Jaroslav Rossler

- Jiri Sigut

- Nadia Rovderova

- Ales Kunes

- Suzanne Pastor

- Jan Saudek

- Villem Reichmann

- Josef Sudek

- Jan Svoboda

- Ladislav Emil Berka

- China

- Iberoamerikanische Fotografie

- EMOP 2025 Landingpage

- EMOP 2025 SHOP

- Artists

- Über uns

- AI-Edition

- Editionen

- Shop

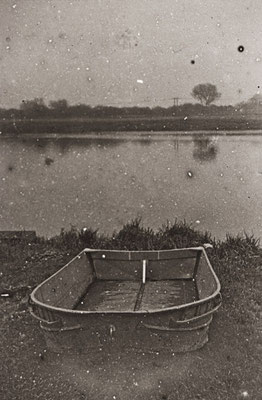

JEREMY LYNCH

Soup

About the work:

Environment : Looking for Inexpensive Photo Processing? Try Lake Ontario : The waterway is so full of polluting chemicals it actually can develop photographs. At least, that's what one local photographer says. And he has the black and whites to prove it.

First it was the Cuyahoga, the river in Cleveland that was so polluted it caught fire. Now, there's Lake Ontario, the lake that's so full of chemicals it develops photographs.

Or so says Jeremy Lynch, a third-year photography student at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute here. Lynch has a portfolio of black-and-white pictures of the Toronto lake front developed, he says, in water from the lake itself. He says he added no chemicals.

"It's really scary," said Lynch. "I have one print that's almost like a regular photograph," so perfect is the quality of the image.

Officials at Eastman Kodak say they are skeptical of Lynch's claims, but his professor at Ryerson, Bill Scanlon, stands behind his student.

"He's not pulling the wool over anybody's eyes, by any means," Scanlon said. "People have done this before, but nobody paid that much attention."

Nor does it come as any surprise to Toronto environmental and health officials that something is wrong with Lake Ontario, the source of this city's drinking water. "This gives us a bit of a picture of the state of the water today," said Bob Pickett, Toronto's assistant director of water pollution control.

Lynch got interested in the photographic potential of lake water last spring, when he was drinking in a bar with some friends and a heavy rain was falling outside. Lynch gazed out at the downpour and thought about acid rain, which has been killing marine life in the lakes of southern Ontario for years.

"I knew acid rain doesn't develop film," Lynch says, but he began thinking that maybe lake water would.

The photographer says he first called various provincial environmental officials to ask where he could find water heavily contaminated with mercury and iron, chemicals that were used to develop daguerreotypes in the early years of photography. The officials refused to give out such information, he says, so he set off by himself to the Lake Ontario shoreline. He took samples of water from near places that struck him as promising: factories, a shipyard, an airport, a beach, the mouth of a canal, a ferry landing.

"Of course, I did it in the worst possible places," he says, adding that he made his rounds on calm days, when there were no waves to disperse the scum floating at the water's edge.

Next, Lynch exposed some film and put it into film-developing canisters with his various water samples.

Darkroom chemicals take about 10 minutes to develop a roll of film, but lake water turns out to take a lot longer. Lynch says he started developing his film at 8 a.m., and the negatives didn't come up on the film until the afternoon of the following day. Lynch said he swirled the contents of the canisters every half an hour or so, to keep the pollutants dispersed in the water. He says he spent the night hitting the 20-minute "snooze" bar on his alarm clock to do so.

Some water samples produced no negatives. Water from the beach, for instance, was full of bacteria that ate the emulsion off Lynch's film, he says. The best sample for developing turned out to be the one he took at the shipyard, where a rusting old cargo vessel was apparently leaching a lot of iron into the water.

After he had his negatives, Lynch took his water samples to a local chemical recycling plant for a professional analysis. His initial hunch, that mercury in the water was developing the film, proved to be wrong; mercury appeared only in minute quantities. But there was plenty of iron. And the shipyard sample also turned out to contain about 1% diesel fuel, with lesser quantities of motor oil, dye, varnish and paint.

Fuel oils and paints contain some of the same chemicals used in the modern photo-finishing process, Lynch says.

Lynch's portfolio won't win any prizes for aesthetics; the pictures are rudely composed and the tones run generally from white to gray, without many true blacks to add interest. Lynch says he wants it that way. He said he tried to shoot Toronto's lake front the way a tourist with a point-and-shoot camera would, going for simple views rather than thoughtful composition. He likes it that the lake water's suspended grit, fuzz and fibers left ghostly images on his prints.

"Grain the size of golf balls," he says with satisfaction, pointing to a blotchy sky in one of his pictures. He thinks the poor quality of the photographs only adds to their environmental message.

Now that Lynch's Toronto collection is complete, he said he wants to travel to the waterfronts of other great American cities and develop their images in the local waters. Niagara Falls, the Statue of Liberty, Detroit's Renaissance Center--he thinks his treatment of each could provoke thought, or maybe even action, on the part of viewers.

"I think it's going to make people think a lot more," he said. "Shoving something down someone's throat is not as effective as showing him."

MARY WILLIAMS WALSH. Times staff writer

Published in Los Angeles Times.

Toronto, 13. November, 1990

Edition:

30 x 40 cm

Edition 10

Lambda prints

1999-2012